Folders |

The Indelible Duel - An Oral History Of Franklyn Sanchez Vs. Andy Powell In The 1999 Massachusetts All-State Indoor 2-MilePublished by

The Indelible Duel

Franklyn Sanchez, Andy Powell and the Race That Changed Everything

An Oral History by Dave Devine

_____

Look at the world around you. It may seem like an immovable, implacable place. It is not. With the slightest push — in just the right place — it can be tipped. - Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference _____ No one gave Franklyn Sanchez much of a chance. That’s not true. His coach, Jean Olds, certainly believed in him. His fiercely loyal friends and family did. Franklyn believed in himself. But as the 1999 Massachusetts indoor state track and field championship approached in late February, everyone from knowledgeable track fans to fellow competitors expected that Andy Powell, a senior at Oliver Ames, would run away with the 2-mile title. Powell was the defending champion, having stormed to the 1998 win in 8:59.19. He’d claimed national indoor victories in the mile and 2-mile that winter. He was a Millrose Games mile champion, a state titlist in cross country, the Foot Locker Northeast champion. Long considered the heir apparent to Brookline’s Jonathon Riley, one of the top distance runners in the nation Powell’s sophomore year, Powell had, if anything, surpassed Riley’s legacy with his own accomplishments. Sanchez was the kid from Lynn who attended the vocational school. He didn’t start running seriously until 10th grade, the same year Powell ran a 4:09 national sophomore record for the indoor mile. He played baseball in the spring. He was discovered running on a treadmill at the YMCA. He worked out with a local running club because his high school team barely held practice. If Powell was the precocious early achiever, Sanchez was the promising late-bloomer. He had certainly had a meteoric rise in Northeast running circles, contesting tight races with Powell in meets from Boston to Florida, but with the exception of a single cross country race their junior year, the state meet where Powell finished an uncharacteristic sixth, he typically found himself runner-up to his in-state rival. With yet another 2-mile clash looming at the speedy Reggie Lewis track, prep running fans anticipated another good race, another brave effort from Sanchez — and a Powell victory. Those same fans had been spoiled by a steady stream of schoolboy talent emerging from Massachusetts in the late 1990s. Riley, who’d moved to the state from New York as a junior, was only one of the stars. Tony DaRocha, coach for the resurgent Boston public schools program, mentored a citywide roster of standouts that included two-time Foot Locker champion Abdirizak Mohamud, nationally ranked harrier Ben Wessenyeleh, and Said Ahmed, national 800-meter champion indoors as a sophomore. Add in Sanchez, Gloucester’s Tristan Colangelo, and a host of others nipping at their heels, and it represented an embarrassment of riches for the Bay State. And even among that lineup, Powell seemed a step apart. If things went well, he expected to threaten Riley’s 8:58.84 meet record, set three years earlier. If he had a great day, Alberto Salazar’s all-time state and New England record of 8:57.4 would be in play. In either case, he’d likely have to do much of the work alone, especially in the second stanza. That’s what Powell figured when he toed the line at the Reggie Lewis Center on that February day in 1999. It’s what most of the raucous, assembled fans presumed as well. They expected to watch Powell pursue a sub-nine minute 2-mile. Instead, they witnessed history. Sanchez and Powell authored a 16-lap masterpiece, a race so jaw-dropping that it stunned everyone in the building and heralded the advent of a long-awaited, almost seismic shift in American schoolboy running. It was the sort of vacillating, give-no-quarter exchange that singes to memory. A heavyweight bout, complete with an intoxicating opening flurry, a dramatic shift, an apparent knockout punch and a last-gasp scramble from the mat. Sanchez over Powell in the final strides, 8:49.60 to 8:50.29. It was an instant, indelible classic for those fortunate enough to witness from the bleachers, but the 20 years hence suggest it may have been much more than a compelling footrace. By the start of 1999, a well-documented decline from the record-setting peaks of the 1960s and 70s had nearly reached its nadir. By almost any measure, the best days for U.S. boys distance running were long past. It had been more than 30 years since a high schooler had broken four minutes in the mile. Gerry Lindgren’s indoor two-mile record of 8:40.0 was 35 years old, seemingly untouchable. There were three years in the 1990s when not a single U.S. boy broke nine minutes for 3,200 meters or two miles. Three other years when only one prep accomplished the feat. Thirteen years since anyone had breached 8:50 — indoors or out. And while the post-millennial reversal of that trend has been attributed to a confluence of factors, everything from rise of the Internet to inspiration from the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games on home soil, from new movies about Steve Prefontaine, to shifting high school demographics, one piece of the narrative is incontrovertible. The turnaround wasn’t gradual. The improvement was sudden and pronounced, beginning with the 1999 track season. The pieces may have been assembled for a paradigm shift, but like so much kindling, it was waiting for a spark. And while it may be difficult to weigh and unravel the contributing factors, to disentangle causation from effect, if there’s a single race to mark the moment boys’ distance running began to recover in the United States, when the long, gnawing regression abruptly and dramatically pivoted, this race is as good a candidate as any. Sanchez and Powell, dropping 8:49 and 8:50 at a state meet in February. Not some big regional invitational or a sprawling, multi-day national championship. Not an evening, eight-lap set-up in a cool coastal clime. The Massachusetts All-State meet. It was still the early days of the Internet, but the race was covered on DyeStat and various rudimentary message boards. News spread via the more conventional means of the day, too: word of mouth, phone calls on landlines, emails on dial-up connection. From the DyeStat Archives - Distance Gods, by Steve Underwood Newsletters and magazines a month later. Did you hear what the two kids in Massachusetts did? It was a race that ignited the imagination, redefining “fast” for a new generation of high school harriers. It helped make a largely moribund event — the grinding 2-mile or 3,200 meters — cool again. And it happened on a cold day in February, 20 years ago, when two friends pushed each other to the limits of their capabilities. Two boys — now men — who are bound forever by a race, a clock, and an unthinkable outcome. This is the story of that day, told in their words, and in the voices of those who witnessed, participated and contributed.

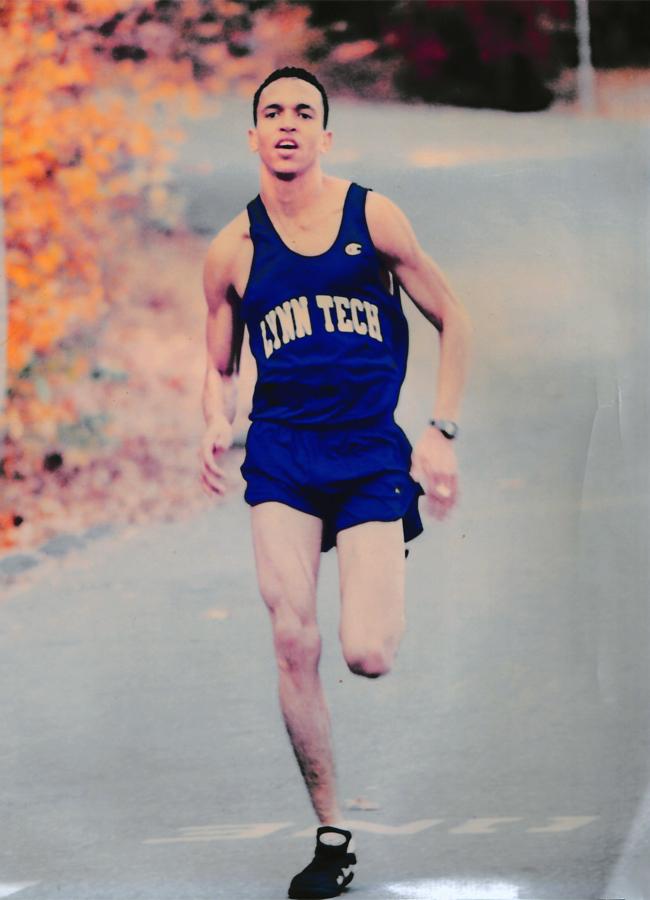

The Voices Franklyn Sanchez – As a senior at Lynn Tech, he was a Foot Locker finalist and national indoor 2-mile champion. Before matriculating to Georgetown University, he spent a year at Cushing Academy in Ashburnham, Mass., winning the USATF junior cross country championship to earn a spot on the World Championship team to Portugal. His freshman year at Georgetown he was sixth at the NCAA Cross Country Championships, and that spring set an American junior record of 13:38.39 for 5,000 meters. After a brief stint with the Nike Oregon Project, he retired from running and is currently a police officer in Maryland.

Andy Powell – He was a two-time Foot Locker finalist, national indoor champion for the mile (twice) and two-mile, and winner at the Millrose Games. As an Oliver Ames senior he won U.S. junior titles in the 1,500- and 5,000-meter runs, and ran a state mile record of 4:02.7. After an injury-shortened career at Stanford University, Powell embarked on a coaching journey that has established him as one of the top distance mentors in the nation. He and his wife, Maurica, spent more than a decade helping re-establish the University of Oregon as a collegiate powerhouse, and are now at the University of Washington as Head Coach (Andy) and Director of Track & Field and Cross Country (Maurica).

Jean (Olds) Cann – Franklyn Sanchez’s coach during his junior and senior years of high school, Cann was an assistant with the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.) running club. She currently coaches girls cross country and track at Hopkinton H.S. in Hopkinton, MA. Paul Carr – Andy Powell’s coach at Oliver Ames High School, Carr led the Tigers to the 1997 and 1998 Massachusetts Division 2 cross country titles, and the 1999 MA Class C indoor track and field championship. He was a coach at Wheaton College for more than a decade, and is currently a senior account manager for UPS, where he’s been for 28 years. Larry Newman – Known to many as “The Voice of New England Track and Field,” he was the meet announcer at the 1999 MIAA Massachusetts All-State Indoor Championships. A retired policeman, Newman is a widely respected historian, statistician and announcer who has worked running events at every level in Massachusetts, including the Boston Marathon. Tom McArdle – A Brookline senior at the time, he was seventh in the 1999 All-State 2-Mile in 9:39.22. McArdle’s career continued at Dartmouth College, where he was a six-time All-American in cross country and track. In 2002, he was the fastest collegian in the nation for 10,000 meters, placing third at the NCAA Outdoor Championships. After graduation, he signed a two-year contract with Nike to become one of the early members of the Nike Oregon Project. He is currently a partner at a Boston consulting firm. Tristan Colangelo – A junior at Gloucester High in 1999, he won the All-State mile that year in 4:18.18. As a senior, Colangelo anchored his Gloucester distance medley relay squad to a 9:59.94 indoor national record that would endure for 17 years. He competed collegiately at Princeton University and is currently a litigation associate for a law firm in Boston. All quotes were provided via phone interview, with the exception of Franklyn Sanchez, who replied over email. Some responses have been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Lead Up Tristan Colangelo (Mile winner): I think we knew it at the time, but Massachusetts, as a fairly small state, we were swinging way above our weight class on the national scene. Paul Carr (Powell’s coach): It was a high watermark for schoolboy running in Massachusetts. Jean Cann (Sanchez’s coach): I think Jonathon Riley moving here was the first thing that spurred things on. Because he moved here from New York and started running all these times that Massachusetts hadn’t seen in a while. Tom McArdle (2-Mile participant): When I was a sophomore, Jonathon Riley broke 9 minutes for two miles, and that was a huge deal. Franklyn Sanchez: Jonathon Riley and Abdirizak Mohamud were a great inspiration. Cann: And then Andy came up.

Andy Powell: Jonathon, my sophomore year, he ended up winning the mile and the two-mile at the indoor nationals. I ran my best time up to that point in the mile — 4:09 — in the race against him. I took the lead from him, because I really wanted to beat him. Carr: We probably knew Andy’s sophomore year we had a real gifted runner. Sanchez: I was a sophomore in high school when I met Jean Cann. She was known as Jean Olds then. Cann: I was the assistant coach for the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.) at the time. There was an older guy in the club who was from Lynn, where Franklyn was from, and he kept seeing Franklyn at the YMCA, running on a treadmill. He started talking to him and was like, ‘You seem really fast, why aren’t you running on a team?’ and Franklyn said, ‘We don’t really have practice, we kind of do our own thing.’ So, he asked Franklyn if he’d like to go to this running club with him. Sanchez: Jerry Powers, one of my high school mentors, used to take me to the B.A.A. running club every Tuesday and Thursday. Cann: The head coach of the B.A.A. at the time was Ed Sheehan…he was the one who initially started giving Franklyn a basic idea of what to do. Then he moved to D.C., and Franklyn started asking me for advice. Sanchez: I was running 10:35 for two miles when Jean and Ed started coaching me. By the end of my indoor track season sophomore year — I played baseball in the spring — Jean and Ed improved my two-mile to 9:33. I ran 9:38 in the (all-state meet) when senior Jonathon Riley and a sensational sophomore, Andy Powell, lapped me on their way to (8:58.84) and (9:06.69). Cann: Franklyn kind of flew under the radar a little bit, because he worked out on his own and trained with the B.A.A. Sanchez: It’s impressive how Jean and I were able to develop such a healthy coach-athlete relationship, and how she was able to gradually and systematically mold me into an athlete. We have a lot in common, but we also grew up very different. Jean was raised on a farm in western Massachusetts, in a small, quiet town called Hinsdale, about 120 miles west of Boston — with hard-working parents. Cann: He grew up in the Dominican Republic until he was 8, then came here. Sanchez: I was raised in an urban city known for violence, called Lynn — referred to as the “City of Sin,” about seven miles north of Boston — with a hard-working, single parent. Cann: Initially, he lived in a one-bedroom apartment with his mom and two brothers. He and his brother had a futon in the living room they both slept on. Sanchez: Two different worlds, and yet Jean knew exactly what worked for me. Cann: It was always his dream to be the first one in his family to go to college…I think running was his way out.

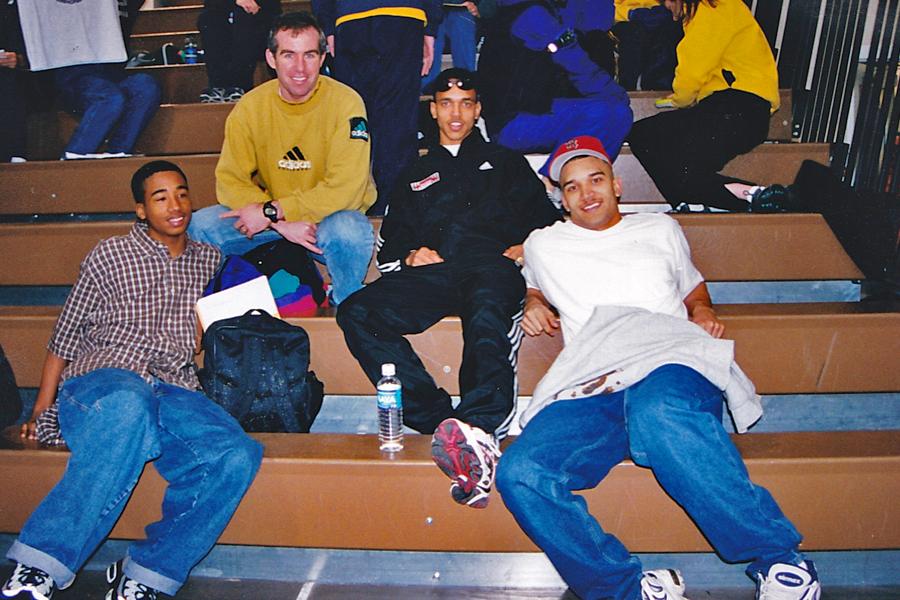

Cann: Andy Powell was still the big name. Powell: Junior year, I ended up trying to do something similar to what Jonathon (Riley) did, mostly because he did it. McArdle: Remember, it was Jonathon who was like, the guy. Powell: So, junior year I won the two-mile at the state meet, and I think I broke nine minutes there. Powell ran 8:59.19 for the win. Sanchez was fourth in 9:28.32. Powell: And I think I was the only one (in the country) that entire year for the full two-miles who broke nine minutes. I got that barrier knocked out. Then I went on to indoor nationals and I won the mile and the two-mile. Cann: Franklyn ran the unseeded section at National Scholastic Indoor that year. Sanchez finished fifth in his heat at 9:25.87. Cann: And then I took him to National Scholastic Outdoor in North Carolina, and his times had really started coming down by then. He got second (9:07.86). McArdle: Even though Franklyn had been second at nationals, he felt new to the sport. He was still pretty raw, even coming into his senior year. Sanchez: Andy and I did some good training during the summer headed into our senior year. Powell: Somehow, Franklyn — and I don’t even remember how it happened — but he got a hold of me at some point, and we went for a run in the summer together. We hammered each other. Like, all-out run. Sanchez: After that, we became good friends. Powell: He’d made this huge jump in cross country. It was clear he’d gotten really, really fit. Carr: The competitive juices went back to cross country in ’98, when they were running the state championship meet. Powell: I guess we were competitive, but it was like, he never wanted to jump me. It was always — let’s both work together. And then we’ll just go to the death at the finish line. Carr: At about the mile mark (of the state cross country meet), there was a pack and I believe Franklyn tapped Andy on the shoulder and said, ‘Let’s go,’ and then those two just took off. Powell: I ended up beating him at the state meet, barely, in cross country. By like a second. Powell won that 2.9-mile race, 14:00 to 14:01. Powell: Foot Locker Regionals — I went hard there. Powell won Foot Locker Northeast in 15:23.2; Sanchez 2nd in 15:41.4. Powell: I tried to win Foot Locker (Nationals) and ended up getting broken down. But the same thing: I was going backwards at Foot Locker, and Franklyn was the one who was like, ‘C’mon, Andy, let’s just finish.’ So even though we were competitive, we ended up helping each other out. Powell was 12th in 15:49.90; Sanchez immediately behind at 13th in 15:50.20. Powell: Then we moved on to indoor track, and it felt like I didn’t hear from him for a while. We ended up racing each other the week before the (All-State) meet. Larry Newman (meet announcer): It was the Class C Meet, and I was announcing. Andy and Franklyn were getting ready for the two-mile, and I was on the infield and Andy came over — not particularly to talk to me, he was taking his sweats off — and I looked at him and I said, ‘Andy, do you think sub-nine today?’ And he throws his sweats on the ground, right in front of me, and says, ‘Just depends on the announcer.’ And he walks away…I thought, ‘Geez, I better do a good job today.’ Powell: I think I ran 9:05 or 9:07 (actual time: 9:03.53), but I won easily, so I just didn’t think Franklyn would be any kind of challenge at the state meet. Newman: I guess I didn’t do my job. I think he was 9:04, and Franklyn was behind him. Colangelo: By and large, Frankie was always a few steps behind Andy. And as good as everybody knew he was, he hadn’t had that breakout race. He hadn’t really established that he was capable of really giving it to Andy. Cann: Way back when he had run in the 9:30’s, Franklyn had a piece of notebook paper stuck to his living room wall that said, I want to break nine minutes. And at the time, you’re like, ‘Oh wow, that’s a big jump from 9:30.’

Meet Day Powell: I broke nine minutes the year before, so I wanted to try to really get under 8:50 for two miles. Colangelo: Any time Andy was going to step on the track and really give it his all, it was an opportunity to see someone set a record. McArdle: The thing that was exciting heading into that day was not really the race between Franklyn Sanchez and Andy Powell. The thing that was exciting was, How fast is Andy Powell going to run? Powell: Going into the race I was feeling pretty good. Really confident. Sanchez: Days before the race, Jean developed a plan. The plan was to let Andy lead the first mile. After the mile mark, she wanted me to take over the race and test Andy — because Andy was known for having a good kick. McArdle: Andy was going win. It was just exciting to think that maybe Franklyn might — look, Andy was going to win the race. He had the big kick, he’d won nationals indoors. Carr: Our strategy was for Andy to go out and try to continuously lap the field. To use the other runners to pull him through. Powell: I wrote all the splits down on my hand, so I had them pretty dialed-in. I knew exactly what I was going to do. Sanchez: I remember walking inside the Reggie Lewis Center with my brother, Juan; my friend, Francisco; Coach Jean and her husband, Brian. Hours before the race, Juan kept reminding me, ‘Hey, no more Mr. Nice Guy with Andy.’ Cann: I thought he at least had a chance. I know it was an off chance, but he’d beaten Andy in cross country his junior year. And I knew he was in good shape. Powell: I was going to go out super hard and just run by myself. It wasn’t like I was trying to race anyone. Carr: Get out, and get to the point of lapping people as quick as possible. Kind of use them as rabbits, so to speak. But they weren’t really rabbits, they were targets. McArdle: I got lapped. I might’ve gotten lapped twice that day. Sanchez: Thirty minutes before the race, Juan says to me, ‘Today, Powell is not your friend, Franklyn. Today he’s your enemy. We going to war today.’ Carr: We were also trying to win a state championship for our (Oliver Ames) team. So, we were sort of counting on that 10 points. Because we had a dual purpose — not only individual, but also team. Cann: Coming out on the track with Franklyn for the two-mile, Andy’s teammate from Oliver Ames, Chris Johnson, was running the 1,000, and he had an off day — he was last in the fast section. Sanchez: Jean whispered to me that Chris had a bad day in the 1,000 meters, and I said to Jean, ‘What if that happens to me? What if I get last?’ Cann: And I said to him, ‘What if it does? What’s going to happen?’ Sanchez: Then Jean and I had a conversation about how there’s always another race, and losing isn’t the end of the world. Cann: You could see him relax after that. Sanchez: I told myself I had nothing to lose.

The Race McArdle: The Reggie Lewis was packed. It was at 100 percent capacity. Newman: The excitement was certainly building up for the race, there’s no question about that. I had done some research at home, just in case they dipped under nine, so I’d know where they might be on the all-time lists. Carr: I remember exactly where I was standing. I was between two sets of bleachers, maybe a couple yards beyond the finish line, on the outside of the track. Colangelo: I was trackside. On the second turn, coming into the homestretch. That’s where we sat. Cann: I was on the far turn, right before the last straightaway. Newman: The atmosphere — it was electrifying, even before the gun sounded. Sanchez: When I stepped to the line, Andy was in Lane 1 and I was next to him, in Lane 2. Andy looked relaxed, and I felt the butterflies. McArdle: I saw Franklyn, and he seemed nervous; I didn’t understand why. He was a good friend, but there was nothing to be nervous about. Andy was going to beat him, and Franklyn would try to run a fast time. Sanchez: The gun went off and I immediately positioned myself behind Andy.

McArdle: It was really loud, right out of the gate. Carr: I’ve never heard any place as loud as I heard the Reggie Lewis that day. I had an assistant coach sitting off my shoulder who couldn’t hear anything I was saying. Sanchez: We went out fast — 2:08 through 800 — and I was simply looking at Andy’s back, just thinking about one thing: the mile mark, and Jean’s strategy to take over the race. Colangelo: For the first mile, it went exactly according to script. Andy took it out hard, and Frankie was just…right there. That’s exactly how everybody expected it to play. Powell: I came through pretty aggressively the first mile — like 4:20, low 4:20s — and it was good. It was crazy, because it was so loud, but it was good. Newman: I’m definitely going to say I announced four-twenty-one. And I was a little shell-shocked. Colangelo: You can’t lose sight of this: I ran the mile, I think I won it in 4:18, and these guys come through the mile in 4:21 — they’re killing it. And it’s a knowledgeable crowd. Everybody knew what they were doing. Cann: That was Franklyn’s PR in the mile, during the two-mile. Going through in 4:21. Newman: I ran over to Dave Ryan — this is the guy doing the manual timing, even though we still had the F.A.T. system going — and I said, ‘David, did we miscount the laps? Is that right?’ And he looks and says, ‘Yeah, 4:21 at the mile.’ That really put me on notice.

Powell: He passed me, and I was totally shocked. I just figured, if I go out like that, no one’s going to be— Cann: Franklyn looked like he was hanging on for dear life, and then I saw him go by and I thought, ‘My word, he’s still got something!’ Sanchez: I think I shook Andy psychologically at that point. Colangelo: When he made that move, that’s when it ratcheted up to the next level. Sanchez: Andy was not expecting me. Powell: I thought I was by myself, so I was really surprised. Newman: It caught all of us by surprise. Carr: I’m thinking, ‘Okay, Franklyn is making his move now, that’s fine. Let him make his move.’ I knew Andy’s workouts; I knew he was tough as nails. Colangelo: I’d never seen Frankie make a move that early in a race, to try to take out Andy. And that’s when the energy really ramped up, because that was new. That was different. And he looked good when he did it — he looked real good. Powell: But he kind of did it like he always did. He passed me, but it wasn’t like he was trying to break me. McArdle: I thought he’d be excited to try to hang on to Andy for as long as he could. I didn’t think Franklyn was actually thinking about beating him. Colangelo: Frankie got right to the lead and kept pressing the pace, and I think at that point, that’s when the crowd understood: Something special was going on here. Sanchez: I was trying to burn Andy’s legs, but it felt like it wasn’t working, because of how fast Andy took out the race. Newman: Everybody was standing up. There was nobody sitting; they understood the significance of the first mile, and they understood the splits. They were in it. Powell: He kept it going for two laps. Carr: We still had one card to play, and I felt good. I figured we’re okay. Powell: I could tell it was slowing down significantly. Carr: Andy had running intelligence. He was able to look at the clock and calculate out what his splits needed to be. He knew what he was going to have to do. Powell: If I was going to run any kind of time, I had to go. Colangelo: When Andy re-took the lead, it started following the script again. That was not unexpected. And when he did it, he did it with such speed and grace — that was the 4:07 miler coming out. Sanchez: At the mile-and-a-half mark, I was trying my best to hang on to Andy, but he slowly started pulling away. McArdle: Andy lapped me and went by in a blur. He was really rolling. But Franklyn was still right behind him. I remember thinking, ‘That’s amazing, Franklyn’s so close.’ Carr: I don’t know that I was even looking at the clock at that point; I was still trying to figure out how the race was developing. Because, again, we’re trying to get Andy under nine, we’re trying to get 10 points for the team — there was a lot going on. Colangelo: Andy was going to take it to the wire from there. Powell: I thought I could just take it the rest of the way. I didn’t think he’d be able to go.

Sanchez: My brother was on the sideline waving his Boston Red Sox hat. I felt like he was telling me to wake up and not give up. We were in a war. Powell: At that point, I’d broken him and pulled away. Newman: We get to two laps to go, and I’m saying to myself, ‘This is going to be about Andy — what kind of time is he gonna get here?’ McArdle: The place was absolutely deafening. Cann: Powell looked like he’d blown Franklyn away, going into the last three laps. Sanchez: My brother’s words continued to resonate in my mind: Today, Powell is not your friend. Colangelo: All of the sudden, you realize he didn’t break Frankie. Newman: As an announcer, it’s difficult to take the fan out of yourself in a race like that. Powell: I couldn’t hear anyone, because it was so loud, but I’m pretty good with numbers so I knew where I was in relation to wanting to run 8:50. Sanchez: I wasn’t thinking about the pace. I was thinking about a way to survive and dig down deep. I told myself that I was already in deep waters, there was no turning back. Newman: I was excited because the whole place was excited. Colangelo: He gained a step. Then two. Sanchez: With two laps to go, through the corners of my eyes, I could see Jean screaming and cheering me on. Cann: Tom McArdle’s dad was actually standing next to me. I think he wondered, ‘Who is this crazy woman yelling in my ear?’ McArdle: My dad said Franklyn’s coach just started screaming.

Colangelo: At least in my head, I’m going, ‘Frankie’s not going to pull this off, he can’t close that gap.’ Sanchez: With one lap to go, something in my brain told me, ‘Don’t give up.’ Powell: I started to fade a little bit, and I guess he was starting to rally. Sanchez: With half a lap to go I was getting closer and closer to Andy. Powell: It just got loud and blurry, but I honestly thought it was only loud because we were running fast. Colangelo: Step after step, he gained a little. Newman: You could see it in their faces, in their eyes, the concentration level. Sanchez: The crowd was going insane. Colangelo: Frankie, as much as I love him, he’s not known for his speed. It’s not like he’s got this blazing kick that’s been hidden all these years. He’s a distance guy. Cann: Franklyn had this low, efficient stride. Not quite smooth like Powell — Powell had this powerful kick. Newman: Nobody was giving an inch. Carr: I just remember Andy coming around the corner — you could tell he was fighting — and then you could see Franklyn coming. Cann: I’m sure Franklyn couldn’t hear me, but I was trying to scream to him: He’s coming back to you! He’s coming back! Carr: There was just no way to let Andy know. Powell: He gets to me on the last straightaway, and at that point it was all I could do. Colangelo: Frankie doesn’t hesitate— Cann: Powell tried to react. I don’t think he had much left. Colangelo: —It was just foot on the gas, keep going. Sanchez: I was seeing double. I thought my brain was blacking out. Cann: It was all guts at the end. Carr: I remember Franklyn passing, and this is no disrespect to Jean or Franklyn, but it was a disappointment. Because we thought we’d done all the right things. Colangelo: We were all prepared that Andy could run 8:55...8:57... somewhere in that range, but to have him run 8:50-flat and get beat, that was something else. Powell: But it’s kind of the race everyone wants to see, right? The underdog coming from behind. McArdle: I finished, and asked someone, ‘What did Andy run?’ And the guy said, ‘Franklyn won,’ and you just couldn’t compute it. And his time — eight-forty-nine? Colangelo: Anybody who says they expected that to happen was lying. Newman: He shattered Jonathon Riley’s meet record. Shattered Alberto Salazar’s Massachusetts and New England all-time records for indoors. Colangelo: The barrier for us had always been nine minutes, and Andy Powell was a god because he’d broken it. I don’t think Frankie had ever been under, so to see him breaking 8:50 was mind-boggling. McArdle: It seemed just impossible. I thought somebody was playing a joke on me. Sanchez: If you’d said to me, ‘Hey Franklyn, in order to beat Powell today you’ll have to run 8:49.60,’ I would have said, ‘Okay...then today is not the day to beat Powell.’ Cann: It took a while before I wanted to clear that 8:49 from my watch. Newman: I had my book with me — my High School Track record book, by Jack Shepard — so I immediately referenced that, and announced that these guys were the fourth and fifth fastest all-time indoors. Sanchez: I remember taking Andy’s hand — Powell: I pushed him to do a victory lap, and he was like, there was no way he was going to do it by himself. Which I thought was — you know, he’s just a good guy. Sanchez: — we did a victory lap together. Cann: Franklyn was always like that, trying to give the credit to somebody else. Newman: The meet officials held up everything for the victory lap, and that’s not the easiest thing to do with the governing body. Powell: You have a lot of mixed emotions, trying to be a good sport and still take it all in. Cann: Even when Andy tried to run off the track, Franklyn grabbed him and made him stay with him the whole time. Powell: It wasn’t the first time I’d done one, but it was probably the most meaningful. Newman: You have to take a deep breath, exhale, and say, ‘Wow. We’ve gotta move on here.’ But you can’t forget what just happened. Powell: I was pretty sick afterward, and we had a good team, so I had to get ready for the 4x400. I was puking outside for a while, and then I had to come back and run my leg. Carr: The amazing thing is that he came back and anchored our 4x400 to a state championship. Powell: I think I split 49 or 50, and we ended up winning. Carr: We ended up in second place as a team that day to Cambridge Rindge & Latin. Lost by four points. Powell: Of course, you never want to lose a race, but if you know a little bit about Franklyn and where he came from — his background — it was pretty cool. McArdle: It’s incredible what it does for you, because Franklyn didn’t really lose again after that. It wasn’t lightning in a bottle. It was more like a coronation. Carr: I give Franklyn all the respect in the world. At least in my mind, he didn’t come out of nowhere that day and jump onto the scene. He was legit from the beginning, and Jean’s a hell of a coach. Sanchez: Jean thought I was ready to run 8:55. But I didn’t think we were going to run sub-8:50 that day. Maybe Jean did, and she just kept it to herself. Cann: All I could think about was that notebook paper on Franklyn’s wall. It had been his vision all along.

The Legacy Colangelo: Before that (race), generally speaking, the times were stagnant. They were slower. You had good individuals here and there, but all the records — all the big distance records — had been set long ago. Powell: It was a really interesting era, because it was pre-Internet. I’d get Track and Field News, but that was mailed out. My family, we never had a computer; we didn’t have a lot of money, so I never had a computer — or a cell phone — until college. McArdle: Sharif Karie, Gabe Jennings, and Jon Riley had made a run at four minutes that was pretty seminal (in 1997). That broke open the attack on good times again in the mile. But those guys hadn’t run that well over two miles. Cann: After Franklyn and Andy ran their two-mile, it wasn’t just the race you did if you weren’t fast enough for the mile. It was a legit, competitive event. McArdle: There was a paradigm shift, where to be someone who had run a remarkable race, you needed to be 8:40-something after that. Colangelo: Today? It probably happens fairly regularly. But then? Practically unheard of — it just didn’t happen. McArdle: But once the door gets kicked open… Colangelo: It certainly indicated what was about to occur in the sport. Newman: At the time, there were only three individuals ahead of Franklyn and Andy, so they went to fourth and fifth on the all-time indoor list. They are currently, I believe, 14th and 15th on that list. Which does show you the progress that’s been made. Colangelo: It was sort of the start of the wave. From then on, the times got faster. Powell: After that, the biggest thing that I’ve seen is the Internet. The more you can see what other people are doing… Sanchez: I do believe Andy’s 8:50 and my 8:49 for two-miles during that era opened the door for runners like Sage, Webb, Ritz, and Solinsky. They were able to perform at that level and surpass those times. Powell: Webb, Ritz, Hall — they saw what people ran and they wanted to one-up them. And they also had each other, which was a really important thing for those guys. Newman: I’ve had some wonderful races to announce, but in the totality of things, the way the race developed, the setting, those two guys…it was probably the high school memory of my career. McArdle: Looking back…Andy was a great runner, don’t get me wrong. Andy was really, really good. But I think Franklyn was actually the transformational talent. Even though, going into that race, everyone thought it was Andy. Cann: I don’t think he ever fully realized how talented he was. Sanchez: A few days ago, I had a chance to go back to the Reggie Lewis Center in Massachusetts. I was inducted into the Massachusetts State Track Coaches Hall of Fame. When I received the award, I couldn’t believe the amount of support. It brought back so many memories. I felt extremely lucky that after 20 years, Massachusetts still remembers me and Andy.

|

Carr:

Carr:  Sanchez:

Sanchez:  Powell:

Powell:  Sanchez:

Sanchez:

Newman:

Newman: